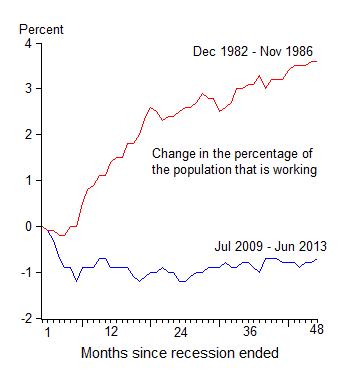

The June employment report released last Friday marks the 48th month of recovery from the recession which ended back in June 2009. We should be pleased that more jobs were created this June, but the disappointing fact is that job growth has not kept pace with population growth during the now four full years of recovery, so a smaller percentage of the working age population has a job than when the recovery began. This chart, which is an updated version of a favorite I have been using throughout the recovery, shows that the employment to population ratio “changed little in June.” as the BLS put it in the release, and has yet to take off after four years.

Last year there was a hot debate involving Mike Bordo, Paul Krugman, Martin Wolf and many others (see here and here) about whether this recovery has been abnormally weak compared to previous US recoveries from deep recessions. After another year of disappointing economic growth, you hear much less debate. The disagreement has shifted from whether to why the recovery has been so weak.

Top on my list of reasons has been economic policy, from its growing unpredictability to the expanded scope of the federal government in certain areas of the economy. It was a Great Deviation from policies that had worked well in the 1980s, 1990s and until recently as explained in First Principles: Five Keys to Restoring America’s Prosperity. What a disappointment policy has been.