Tomorrow Stanford embarks on a new principles of economics course at the introductory level. For the first time since the financial crisis we will be teaching the course in one term. I will be doing the inaugural course consisting of 35 fifty-minute lectures assisted by a team of teaching fellows who will lead 10 additional small discussion sections throughout the term.

We are moving to a single one-term course that combines micro and macro from two courses–one on micro and one on macro–for a number of internal reasons, including the need to provide a complete one-term course for students not majoring in economics. In fact, before Stanford offered a two-course sequence, it offered a one-term course for many years, so it is not entirely foreign to the curriculum.

In my view, there are also pedagogical reasons to make this change. I think it is time for a course that better integrates micro and macro. There were arguments for doing this before the crisis, including the fact that in research and graduate teaching the tools of micro have been better integrated into macro, but the financial crisis clinches the case in my view. The crisis along with the slow recovery and other associated changes is the biggest economic event in decades, and it can only be understood with a mix of micro and macro. To understand recent events one must know about supply and demand for housing (micro), interest rates that may have been too low for too long (macro), moral hazard (micro), a stimulus package (macro) aimed at such things as health care (micro), a new type of monetary policy (macro) that focuses on specific sectors (micro), debates about the size of the multiplier (macro), excessive risk taking (micro), a great recession (macro), and so on. It you look at any explanation of the crisis and the slow recovery, you’ll see a mix of micro and macro.

Moreover, the introductory course can be integrated in a way that makes economics more interesting for students. I have been experimenting with this. When I talk about aggregate investment demand I say it came right out of the micro demand for capital. Similarly aggregate employment and unemployment can be explained in the context of micro labor supply and demand. The proof that aggregate production (GDP) equals aggregate income can be stated at the time one defines profits as equal to revenues minus cost of labor and capital. The demand for money as a function of the interest rate is easily explained with the opportunity cost concept.

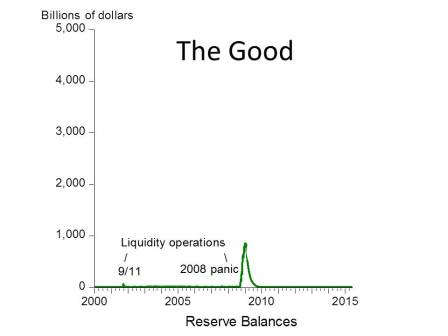

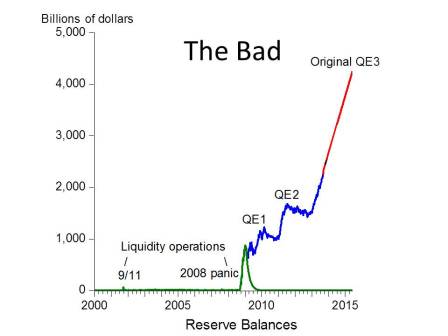

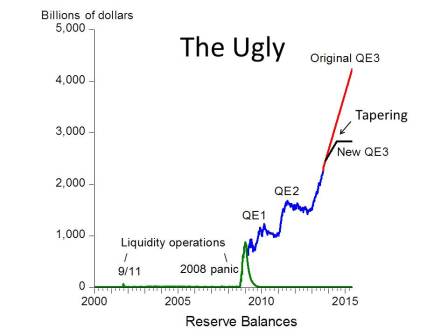

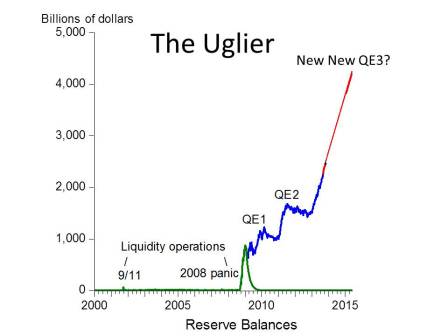

I think this approach works no matter what your view is of the crisis and the policy response. In my view the problem was that economic policy deviated from basic economic principles which had worked well. The result was a great recession, a financial panic, and now a slow recovery. The deviations included a monetary policy which set interest rates too low for too long and a regulatory policy which failed to enforce existing rules. The deviations from sound principles then continued. The good news for the economy is that economic growth and stability can be restored by adopting policies consistent with basic economic principles.

Of course there are other views, but the heated disagreement among economists about the crisis, its causes, and its aftermath presents a great opportunity to make economics more interesting.

By the way, 35 lectures in a one-quarter term may seem like a lot, but that is one reason why we can take this approach. In contrast, the macro principles course at Princeton has had only 12 lectures in a semester and the micro principles course has had 24 lectures. I understand that the Economics 10 course at Harvard has only about a half dozen lectures per semester by the main professor, with guest lecturers filling in for another half dozen.