This past week the Transportation Research Board released its Special Report from the “Committee on Economic and Employment Benefits of Transportation Investments in Response to Economic Downturns.” The report evaluated the 2009 stimulus and in particular the part of the stimulus that provided grants to states for transportation infrastructure. The Transportation Research Board is part of the National Research Council, the principle operating agency of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Engineering.

The report has two main parts, the first on fiscal stimulus packages in general and the second on the design and workings of the 2009 stimulus. The design part usefully examines a number of practical problems with the stimulus, such as the “maintenance-of-effort” requirements in which the states were supposed to maintain expenditures of state funds so that the federal stimulus grants (ARRA) would not simply replace state funding. In practice the states and federal government experienced many difficulties in “interpreting, administering, and complying with ARRA’s maintenance-of-effort requirement” the Committee reports.

Based on this experience the report makes recommendations on how to avoid such problems if another stimulus is considered in the future. It’s a concern, however, that the report does not examine why similar lessons from previous discretionary stimulus packages, such as the stimulus packages in the 1970s studied by Ned Gramlich and others, were not sufficiently reflected in the design of the 2009 package. Perhaps there are real feasibility problems with such stimulus packages.

But a greater concern pertains to the first part of the report which does not accurately characterize the existing evidence on discretionary fiscal stimulus packages. The report argues that “the preponderance of studies support the conclusion that federal stimulus spending, during a recession or period of high unemployment and when monetary policy is maintaining low interest rates, leads to an increase in gross domestic product (GDP) and in employment, at least in the short term (within 1 or 2 years after the spending)….Research based on experience since 2008 tends to support values of the multiplier above 1 as applicable when unemployment is severe and interest rates are being held near zero.”

Having done research on this topic since 2008 I noticed that the report fails to refer, for example, to a 2009 study by Cogan, Cwik, Wieland and me (CCTW), later published here, which found multipliers below 1. This was one of the first model-based calculations of the government purchases multiplier for the 2009 stimulus. Nor does the report refer to the calculations reported by numerous economists at research departments at central banks and international financial institutions, who largely came to the same conclusion as CCTW.

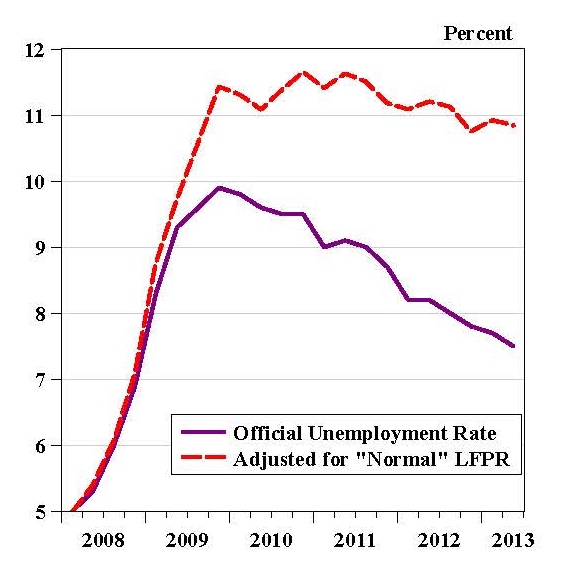

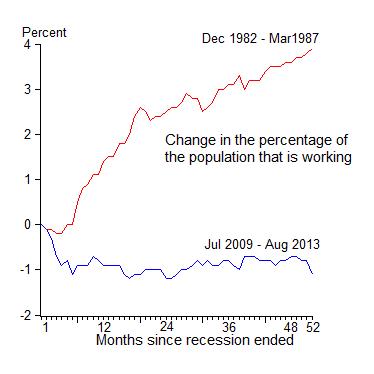

Fortunately, one of the Committee members, Bill Dupor, who refused to go along with the Committee’s report, has written a thoughtful statement explaining these and many other concerns about the report. His dissenting statement is found in Appendix B of the report. Bill Dupor has done a lot of original research on the 2009 stimulus package and he knows as much as anyone about the program, the data, the models, and the econometrics. He raises a number of issues and provides data not included in the body of the report. For example, he points out that despite the enormous scale of the federal stimulus grants there was no visible impact on employment, which by one important measure declined as shown in this chart from his statement.

One can always say that things would have been worse without the federal grants, but the scale of the grants was so large that this explanation of the figure is hard to take seriously. Dupor’s explanation for the lack of a larger impact from the grants is that many states found other things to do with the funds, which is similar to the conclusion of John Cogan and me in another paper (see p 85-114 of this book on line).

Considering these impacts and the difficulty of any design changes in our federal system, Bill Dupor concludes: “Weighing these factors together, I suggest that policy makers consider not using stimulus spending at all regardless of category,” adding that “economic theory permitted economists to foresee some of the problems with the Recovery Act beginning decades ago.” I agree.