New Yorker writer John Cassidy argues in a recent article that free market-oriented Chicago school thinking was largely responsible for the financial crisis, and that, for this reason, interventionist-oriented Keynesian thinking has rightly replaced Chicago, which had previously “greatly influenced policy making in the United States.”

Cassidy makes his case mainly through a star witness, Judge Richard Posner, who Cassidy says “has shocked the Chicago School by joining the Keynesian revival.” Cassidy also reports the views of other University of Chicago economists about the Chicago School and its influence, but he dismisses many of them out of hand, especially John Cochrane and Gene Fama, who he calls “true believers” or “in the denial camp.” To his credit, Cassidy posted his interviews with these other economists on his blog. Nevertheless, relying on the interpretations of opinions of Posner or anyone else is an inherently subjective way to characterize a school of thought or to measure the extent of its influence on policy making.

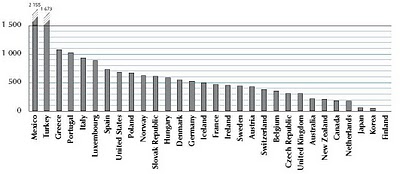

Are there more objective, perhaps quantitative, ways? Consider, for example, measuring influence by the representation of members of a school in top economic positions in government where there is an opportunity to influence policy. And consider as a measure of an economist’s school, the university where he or she received the PhD. The data in the chart follows this approach. It shows the university PhD percentages of appointees to the President’s Council of Economics Advisers (CEA).

The blue line shows the percentage of presidential appointees to the CEA who have a PhD from Chicago. The red line shows the same for MIT or Harvard (Cambridge), one possible definition of an alternative to the Chicago school. The years from the creation of the CEA in 1946 until 1980 are shown along with each presidential term thereafter. Observe that the peak of the Chicago school influence was in the Reagan administration; it then dropped off markedly. In contrast Cambridge reached a low point of zero appointees to the CEA during the Reagan administration and then rose slightly to 20 percent in Bush 41, to 82 percent in Clinton, and to 100 percent in both Bush 43 and in Obama.

Blaming the financial crisis on the free-market influence of the Chicago school is certainly not consistent with these data. There were no Chicago PhDs on the President’s CEA leading up to or during the financial crisis. In contrast there was a great influx and then dominance of PhDs from Cambridge. And also notice that there were plenty of Chicago PhDs on the CEA at the time of the start of the Great Moderation—20 plus years of excellent economic performance. These data are more consistent with the view that the waning of the free-market Chicago school and the rise of interventionist alternatives was largely responsible for the crisis. But the main point is that there is no evidence here for blaming the influence of Chicago.

Of course, such measures are imperfect. Neither Milton Friedman nor Paul Samuelson served on the CEA, but their students did. And while PhDs from any insitution certainly do not fit in any one mold, the people who learned about rules versus discretion with Friedman likely had a different policy approach than people who learned about rules versus discretion with Samuelson. The data are robust when you look beyond the CEA to other top posts normally held by PhD economists. All assistant secretaries of Treasury for Economic Policy appointed during the Bush 43 and Obama Administrations had PhDs from Harvard. During the same period, all chief economists appointed to the IMF had PhDs from MIT, and, except for Don Kohn, who was promoted from within and Susan Bies who was appointed as a banker, all PhD economists appointed to the Federal Reserve Board were from Cambridge MA.

In the next chart you see the contribution of consumption, which plays a noticeable but considerably smaller role.

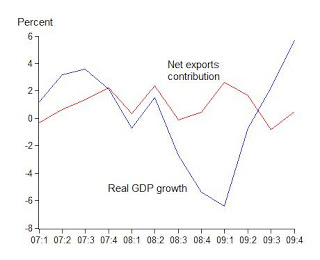

In the next chart you see the contribution of consumption, which plays a noticeable but considerably smaller role.  The third chart shows the contribution of net exports, which explains some of the smaller movements in early 2008.

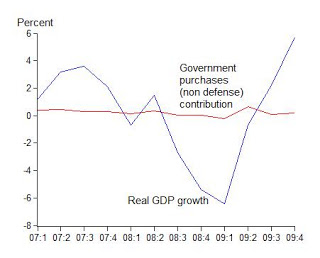

The third chart shows the contribution of net exports, which explains some of the smaller movements in early 2008.  The fourth chart shows the contribution of government purchases. I have focused on non-defense federal plus state and local purchases because defense spending was not part of the stimulus (adding in defense does not change the story). Note that none of the action in real GDP growth is due to government purchases.

The fourth chart shows the contribution of government purchases. I have focused on non-defense federal plus state and local purchases because defense spending was not part of the stimulus (adding in defense does not change the story). Note that none of the action in real GDP growth is due to government purchases.  In other words during the entire first year of the stimulus package, the contribution of government purchases to change in real GDP growth is virtually nil. There is no evidence here that the stimulus has worked either to raise GDP growth or to create jobs.

In other words during the entire first year of the stimulus package, the contribution of government purchases to change in real GDP growth is virtually nil. There is no evidence here that the stimulus has worked either to raise GDP growth or to create jobs.

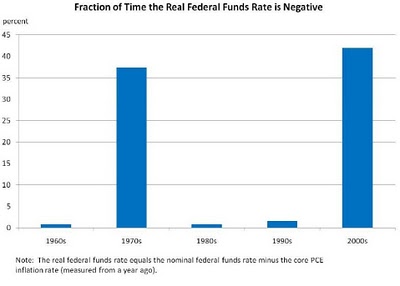

Also some asked about the specific reference to the finding of Athanasios Orphanides and Volker Wieland that interest rate were too low for too long if you use private sector forecasts of inflation rather than the Fed’s forecasts in the Taylor rule. Here is the

Also some asked about the specific reference to the finding of Athanasios Orphanides and Volker Wieland that interest rate were too low for too long if you use private sector forecasts of inflation rather than the Fed’s forecasts in the Taylor rule. Here is the