Polls show that most Americans don’t believe that the stimulus package worked, but debate continues among economists. The most debated issue is the size of government purchases multiplier. Suppose that the government purchases multiplier is 1.5. Then Economics 1 students learn that the change in GDP due to an increase in government purchases is found by multiplying the change in government purchases by 1.5. That is:

change in GDP =1.5 times change in government purchases

Government purchases include spending on items such as infrastructure, law enforcement, and education, but do not include interest and transfer payments. (A derivation is in Ch. 23 appendix of the Taylor-Weerapana principles text.)

The example of 1.5 is at the upper range of estimates, and was used in a paper by Christina Romer and Jared Bernstein to estimate the impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA). However, John Cogan, Volker Wieland, Tobias Cwik, and I found that the multiplier in the case of ARRA was much smaller, around .7. Robert Barro argues that it is zero. So there is debate.

But few have focused on the second term in the above multiplier formula: the change in government purchases due to ARRA. John Cogan and I have been tracking data on the changes in government purchases since ARRA was passed, using a new data series provided by the Commerce Department. We just finished a working paper reporting the details of our findings, which provide additional evidence that the stimulus has not worked and, just as important, on why it has not worked.

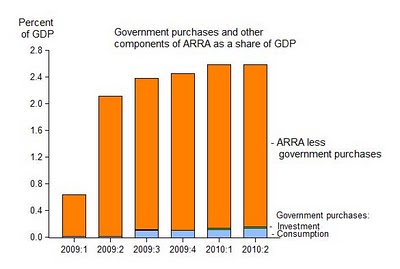

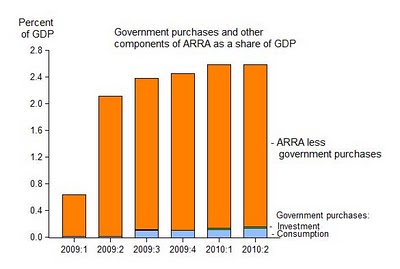

Despite the gigantic $862 billion stimulus package, the change in government purchases due to ARRA has been immaterial to the economic recovery: government purchases increased by only 2 percent of the $862 billion package ($18 billion). Infrastructure was even less at $2.4 billion. There has been almost no change in government purchases for the multiplier to multiply. It’s no wonder people don’t think the stimulus worked. And the size of the multiplier is largely irrelevant!

Our research looks at both federal and state and local purchases. Federal purchases due to ARRA reported by the Commerce Department are very small. We also find that large ARRA grants to the states did not increase state and local government purchases at all. To check our results we traced where the grant money went (it went mainly to reduce state borrowing) and we considered counterfactuals (in the absence of ARRA, government purchases would likely have been higher). The chart below summarizes the findings with all the government purchases at the federal level. The implication of this research is not that the stimulus program was too small, but rather that such countercyclical programs are inherently limited by feasibility constraints of the federal system.  John Cogan and I first reported these results in a preliminary way over a year ago in a September 16, 2009 a Wall Street Journal article with Volker Wieland, entitled “The Stimulus Didn’t Work”. Though ARRA data were then only available through the second quarter of 2009, it was clear to us that government purchases were not contributing to the recovery, and we reported that “there is no plausible role for the fiscal stimulus here.” Many dismissed our conclusion, saying it was too soon to judge. Another year of data has confirmed our results as we explain in our new working paper.

John Cogan and I first reported these results in a preliminary way over a year ago in a September 16, 2009 a Wall Street Journal article with Volker Wieland, entitled “The Stimulus Didn’t Work”. Though ARRA data were then only available through the second quarter of 2009, it was clear to us that government purchases were not contributing to the recovery, and we reported that “there is no plausible role for the fiscal stimulus here.” Many dismissed our conclusion, saying it was too soon to judge. Another year of data has confirmed our results as we explain in our new working paper.

One logical date is August 27, the day of Ben Bernanke’s Jackson Hole speech where he discussed the framework of quantitative easing in detail. Indeed, this Jackson Hole speech is frequently mentioned in the financial press. The date of the speech is shown in the chart. The long-term rate was 2.66 percent on that date. If anticipations of quantitative easing lowered long-term interest rates, then one would expect this rate to have been lower on November 2, the day before the FOMC’s recent action. But this is not what happened. The interest rate was the same 2.66 percent on November 2 as it was on August 27.

One logical date is August 27, the day of Ben Bernanke’s Jackson Hole speech where he discussed the framework of quantitative easing in detail. Indeed, this Jackson Hole speech is frequently mentioned in the financial press. The date of the speech is shown in the chart. The long-term rate was 2.66 percent on that date. If anticipations of quantitative easing lowered long-term interest rates, then one would expect this rate to have been lower on November 2, the day before the FOMC’s recent action. But this is not what happened. The interest rate was the same 2.66 percent on November 2 as it was on August 27.

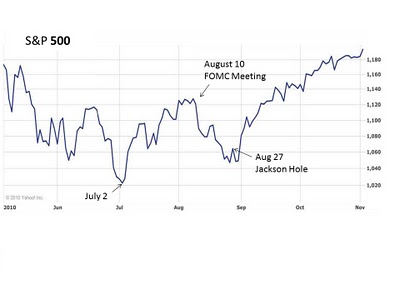

Next consider stock prices. The third chart shows the S&P 500 index over the same period. Observe that the current rally began in early July as shown in the chart. Evidently concerns about a double dip recession had diminished by early July and earnings reports began improving. From July 2 to August 10 the S&P 500 rallied by 10 percent. That rally was temporarily interrupted starting on August 10, but then continued. From August 10 to November 2 the S&P 500 rose another 7 percent.

Next consider stock prices. The third chart shows the S&P 500 index over the same period. Observe that the current rally began in early July as shown in the chart. Evidently concerns about a double dip recession had diminished by early July and earnings reports began improving. From July 2 to August 10 the S&P 500 rallied by 10 percent. That rally was temporarily interrupted starting on August 10, but then continued. From August 10 to November 2 the S&P 500 rose another 7 percent.

John Cogan and I first reported these results in a preliminary way over a year ago in a September 16, 2009 a Wall Street Journal article with Volker Wieland, entitled “

John Cogan and I first reported these results in a preliminary way over a year ago in a September 16, 2009 a Wall Street Journal article with Volker Wieland, entitled “