Categories

Archives

A New Chart Cast on the Bad News Recovery

As many have observed the employment report for August released today was disappointing news, but it really is a continuation of a steady stream of bad employment news that has been the story of this recovery since its beginning. The economy is growing too slowly to increase jobs at a pace that matches the growing population—unlike previous recoveries from deep recessions.

Here is an update of the chart that compares the change in the employment to population ratio in this recovery with the recovery from the deep slump of the early 1980s. This percentage dropped a litttle in August, but the big story is that there has never been a lift off.

Russ Roberts has produced a fascinating a new “chartcast” which illustrates how unusually poor this recovery has been. Through a series of questions and answers he traces through several key charts with me. It is a visual version of his very successful podcast series Econ Talk.

Russ is planning a follow-up chartcast which gets into the causes of the slow recovery.

Posted in Slow Recovery

Comments Off on A New Chart Cast on the Bad News Recovery

Strong Push Back at Jackson Hole

In his Jackson Hole speech, Ben Bernanke argued that quantitative easing (in particular Large Scale Asset Purchases, or LSAPs) has had large macroeconomic effects, saying that “a study using the Board’s FRB/US model of the economy found that, as of 2012, the first two rounds of LSAPs may have raised the level of output by almost 3 percent and increased private payroll employment by more than 2 million jobs, relative to what otherwise would have occurred.” He footnoted a Fed paper by Hess Chung et al, in which the authors plugged in other people’s estimates of the impact of LSAPs on long term rates into the FRB/US model which does not have its own estimates.

However, a number of conference participants pushed back on this view, including John Ryding of RDQ, Mickey Levy of Bank of American and me, but most of all Michael Woodford whose paper showed in detail how empirical evidence and basic economic theory did not support these beneficial effects.

Woodford’s empirical evidence included a simple graph (Fig 15) showing that there was no economic growth effect around the times of the expansions in the size of the Fed’s balance and thus that the quantitative easing had “little evident effect on aggregate nominal expenditure…”

He challenged the view that the LSAPs lowered long term rates or at least had the kind of impact assumed by Chung et al. He explained that “‘portfolio-balance effects’ do not exist in a modern, general-equilibrium theory of asset prices…” which is what many of us have been teaching students for thirty years.

He questioned the various event studies cited by the Fed, such as Gagnon et al, saying “it is not clear that their announcement-days-only measure should be regarded as correct.”

He showed that the often-cited evidence reported by Arvind Krishnamurthy and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen that “purchases of long-term Treasuries could raise the price of (and so lower the yield on) Treasuries…would not necessarily imply any reduction in other long-term interest rates, since the increase in the price of Treasuries would reflect an increase in the safety premium, and not necessarily any increase in their price apart from the safety premium…This means that while the US Treasury would then be able to finance itself more cheaply at the margin, there would not necessarily be any such benefit for private borrowers, and hence any stimulus to aggregate expenditure….There seems little reason to believe that purchases of long-term Treasuries should be an effective way of lowering the kind of longer-term interest rates that matter most for stimulating economic activity.”

Woodford also questioned the beneficial impacts of forward guidance as practiced by the Fed so far, saying that “simply presenting a forecast that the policy rate will remain lower for longer than had previously been expected, in the absence of any reason to believe that future policy decisions will be made in a different way, runs the risk of being interpreted as simply an announcement that the future is likely to involve lower real income growth and/or lower inflation than had previously been anticipated — information that, if believed, should have a contractionary rather than an expansionary effect.”

In Woodford’s view, forward guidance could have achieved positive effects if it had “made it clear that short-term interest rates will not immediately be increased as soon as a Taylor rule descriptive of past FOMC behavior would justify a funds rate above 25 basis points,” because “this would provide a reason for market participants to expect easier future monetary and financial conditions than they may currently be anticipating, and that should both ease current financial conditions and provide an incentive for increased spending.”

Many Fed watchers interpreted the benefit-cost analysis in Ben Bernanke’s speech as signaling more quantitative easing. But viewed in the context of the whole Jackson Hole meeting, which many FOMC members attended, the benefits are considerably smaller than stated in that speech, and perhaps even negative.

Posted in Monetary Policy

Comments Off on Strong Push Back at Jackson Hole

Government Policies and the Delayed Economic Recovery

A year ago, when the economic recovery had already been delayed two years, Lee Ohanain and I got the idea for a book on the role policy in the delay. To make the idea operational we invited people who were working on the topic to a conference and to write chapters. The book Government Policies and the Delayed Economic Recovery is now available as an ebook with printed copies on their way to Amazon and other booksellers.With yet another year of delayed recovery and growing debates about the cause, the topic is more relevant than ever.

Here is how Lee Ohanian, Ian Wright and I summarized the papers and their implications in the Introduction:

The contributors to this book consider a wide range of topics and policy issues related to the delayed economic recovery. While their opinions are not always the same, together they reveal a common theme: the delayed recovery has been due to the enactment of poor economic policies and the failure to implement good economic policies. The discussion at the conference where some of the papers were presented—summarized by Ian Wright—reveals a similar theme.

The clear implication is that a change in the direction of economic policy is sorely needed. Simply waiting for economic problems to work themselves out, hoping that growth will improve as the Great Recession of fades into the distant past, will not be enough to restore strong economic growth in America.

And here is the Table of Contents:

Economic Strength and American Leadership

George P. Shultz

Uncertainty Unbundled: The Metrics of Activism

Alan Greenspan

Has Economic Policy Uncertainty Hampered the Recovery?

Scott R. Baker, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis

How the Financial Crisis Caused Persistent Unemployment

Robert E. Hall

What the Government Purchases Multiplier Actually Multiplied in the 2009 Stimulus Package

John F. Cogan and John B. Taylor

The Great Recession and Delayed Economic Recovery: A Labor Productivity Puzzle?

Ellen R. McGrattan and Edward C. Prescott

Why the U.S. Economy Has Failed to Recover and What Policies Will Promote Growth

Kyle F. Herkenhoff and Lee E. Ohanian

Restoring Sound Economic Policy: Three Views

Alan Greenspan, George P. Shultz, and John H. Cochrane

Summary of the Commentary

Ian J. Wright

Posted in Slow Recovery

Comments Off on Government Policies and the Delayed Economic Recovery

Which Simple Rule for Monetary Policy?

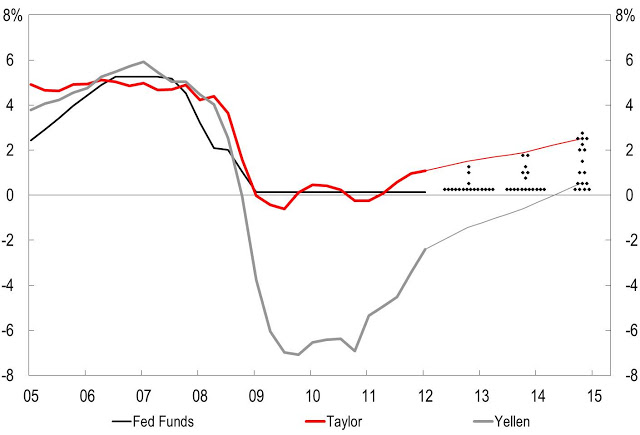

The discussion of “Simple Rules for Monetary Policy” at last week’s FOMC meeting is a promising sign of a desire by some to return to a more rules-based policy. As described in the FOMC minutes, the discussion was about many of the questions raised in recent public speeches by FOMC members Janet Yellen and Bill Dudley. A big question is which simple rule?

Yellen and Dudley discussed two rules. Using Yellen’s notation these are

R = 2 + π + 0.5(π – 2) + 0.5Y

R = 2 + π + 0.5(π – 2) + 1.0Y

where R is the federal funds rate, π is the inflation rate, and Y is the GDP gap. Yellen and Dudley refer to the first equation as the Taylor 1993 Rule and the second equation as the Taylor 1999 Rule, though the second equation was only examined along with other rules, not proposed or endorsed, in a paper I published in 1999.

The two rules are similar in many ways. Both have the interest rate as the instrument of policy, rather than the money supply. Both are simple, having two and only two variables affecting policy decisions. Both have a positive weight on output. Both have a weight on inflation greater than one. Both have a target rate of inflation of 2 percent. Both have an equilibrium real interest rate of 2 percent.

The two rules differ substantially, however, in their interest rate recommendations as this amazing chart constructed last April by Bob DiClementi of Citigroup illustrates. The chart shows two rules along with historical and projected values of the federal funds rate. The rule labeled “Taylor” by DiClementi is the rule I proposed. The other rule is labeled “Yellen” by DiClementi because it corresponds to the rule apparently favored by Yellen. The projected values are the views of FOMC members.

Observe that the first rule never gets much below zero, while the second rule drops way below zero during the recent recession and delayed recovery. The difference continues though it gets smaller into the future. Note that the projected interest rates by FOMC members span the two rules.

This big difference between the two rules in the graph can be traced to two factors: (1) The second rule has a much larger GDP gap, at least as used by Yellen. (2) The second rule has a much bigger coefficient on the GDP gap.

In my view, a smaller value of the GDP gap and a smaller coefficient are more appropriate. This view is based on a survey of estimated gaps by the San Francisco Fed and simulations of models over the years. But given the striking differences in DiClememti’s chart, more research on the issue by people in and out of the Fed would certainly be very useful.

Posted in Monetary Policy

Comments Off on Which Simple Rule for Monetary Policy?

Democracy is Not a Spectator Sport, Even for Economists

It’s good news that economic issues are now getting more attention in the presidential campaign. More than 400 economists have signed a statement on the differences between the Romney economic program and the Obama program—the numbers are growing each day—and economic commentators including on CNBC and the Wall Street Journal (here and here) are discussing it. Judging by the hits on this post on Economics One, there’s a great deal of interest in the issues rasied in the economic white paper—authored by Kevin Hassett, Glenn Hubbard, Greg Mankiw and me—comparing the effects on economic growth of the Romney program and the Obama program. Of course, the selection of Paul Ryan has set off a huge number of articles on economics from budget policy to monetary policy.

It’s already clear to most voters that the presidential candidates have vastly different approaches to economic policy. But many people are still not informed about the implications of these two approaches. In my view the more voters get informed, and the more their votes are based on that information, the more likely the officials they elect will be able to revive the economy.

But this will not happen if the political campaign drifts back away from substance as campaigns so often do. Keeping the debate focused on economics requires that economists participate and not merely sit back and watch. To remind myself of this, I like to wear this “Democracy is not a spectator sport” tie a lot during the election season.

Posted in Teaching Economics

Comments Off on Democracy is Not a Spectator Sport, Even for Economists

Paul Krugman is Wrong

Paul Krugman took time off from his vacation last Friday to take a shot at a paper by Kevin Hassett, Glenn Hubbard, Greg Mankiw and John Taylor on the growth and employment impacts of Governor Romney’s economic program in comparison with President Obama’s program. Though flaming with vitriolic rhetoric, his shot misses the mark.

Half of Krugman’s piece strays away from the paper, so focus on what he actually says about the paper.

First, he says that that the “work of other economists” cited in the paper does not support its position. But the research papers and books that are cited are quoted correctly and do provide supporting evidence. As Scott Sumner reports “when I looked at the paper I couldn’t find a single place where they had misquoted anyone.” And Jim Pethokoukis shows not only that the evidence cited in the paper is supportive, but also that Krugman is on record as previously agreeing with the cited work on the 2009 stimulus package.

Second, Krugman claims that the authors whose work is cited in the paper have also done other work which is not supportive of other aspects of the paper. The example he mentions is the work of Atif Mian and Amir Sufi showing that the slump is “demand-driven” in addition to their cited work on the cash-for-clunkers program (and much other work by the way). But work showing that the slow recovery is demand-driven is not evidence that the Romney program will not increase economic growth. As the paper on the Romney economic program states, the program works in two ways: “It will speed up the recovery in the short run, and it will create stronger sustainable growth in the long run.” Demand and supply are at work.

Third, Krugman asserts that the “Baker et al paper claiming to show that uncertainty is holding back recovery clearly identifies the relevant uncertainty as arising from things like the GOP’s brinksmanship over the debt ceiling — not things like Obamacare.” Well there is nothing about “the GOP’s brinkmanship” in the Baker et al paper; those are Krugman’s words. And the paper on the Romney economic program does not link Baker et al to Obamacare. The Baker et al paper uses an index of policy uncertainty which has been very high in recent years for many reasons including uncertainty about future taxes and the debt problem, as exemplified by the 2011 debt dispute, which had its origins prior to 2011, including in 2009 and 2010. That is exactly the point: Policy uncertainty is high now for a number of reasons, and reducing it with a long-term strategy rather than more short-term fixes will increase economic growth and create jobs.

Posted in Regulatory Policy

Comments Off on Paul Krugman is Wrong

It’s Still a Recovery in Name Only–A Real Tragedy

I have been regularly charting the path of real GDP and employment during the recovery from the recession as new data are released. From the start it was clear that the recovery was very weak. By its second anniversary the recovery was weak for long enough to call it “a recovery in name only, so weak as to be nonexistent.” Now we are just past the third anniversary, and it is still at best a recovery in name only. It’s now the worst in American history—a tragedy that should not be minimalized.

Here’s an update of the charts using the latest data through the second quarter or through July for monthly data. The first one shows real GDP in this recovery. You can see that the gap between real GDP and potential GDP (CBO estimates) is not closing at all. That is the main reason why unemployment remains so high.

Second is the comparison chart with the recovery from the previous deep recession in the early 1980s.That is a typical recovery from a deep recession. The gap closes.

Some say that recoveries from deep U.S. recessions–or from financial crises–are usually slower, but this is simply not true. Below are similar charts from the 1893-94 recession

and from the 1907 recession,

both associated with severe financial crises. You can see the sharp rebounds, nothing like the terrible recovery we have seen recently. This does not imply that the period after these recoveries was smooth; indeed a double dip followed the recovery in the early 1890s.

Of course potential GDP is difficult to measure so it is important to look at alternative charts. The next one used GDP growth rates. The average real GDP growth rate in this recovery has been only 2.2 percent, even lower than the 2.4 percent before the data were revised.

Finally, with today’s July employment numbers you can see the extraordinarily weak employment record in this recovery. The employment-to-population ratio is still lower than at the start of the so-called recovery. We now know that it fell in July as shown in the lower right part of the chart.

Posted in Slow Recovery

Comments Off on It’s Still a Recovery in Name Only–A Real Tragedy

Still Learning from Milton Friedman

We can still learn much from Milton Friedman, who was born 100 years ago today. Here I focus on his role in the macroeconomic debates of the 1960s and 1970s, because they are so similar to the debates raging again today.

Friedman, Samuelson, and Rules Versus Discretion

First, go back to the early 1960s. The Keynesian school was coming to Washington led more than anyone else by Paul Samuelson who advised John F. Kennedy during the 1960 election campaign and recruited people like Walter Heller and James Tobin to serve on Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers. In fact, the Keynesian approach to macro policy received its official Washington introduction when Heller, Tobin, and their colleagues wrote the Kennedy Administration’s first Economic Report of the President, published in 1962.

The Report made an explicit case for discretion rather than rules: “Discretionary budget policy, e.g. changes in tax rates or expenditure programs, is indispensable…. In order to promote economic stability, the government should be able to change quickly tax rates or expenditure programs, and equally able to reverse its actions as circumstances change.” As for monetary policy a “discretionary policy is essential, sometimes to reinforce, sometimes to mitigate or overcome, the monetary consequences of short-run fluctuations of economic activity.”

In that same year Milton Friedman published Capitalism and Freedom (1962) giving the competing view on role of government which he then continued to espouse through the 1960s and beyond. He argued that “the available evidence . . . casts grave doubt on the possibility of producing any fine adjustments in economic activity by fine adjustments in monetary policy—at least in the present state of knowledge . . . There are thus serious limitations to the possibility of a discretionary monetary policy and much danger that such a policy may make matters worse rather than better . . . The basic difficulties and limitations of monetary policy apply with equal force to fiscal policy . . . Political pressures to ‘do something’ . . . are clearly very strong indeed in the existing state of public attitudes. The main moral to be had from these two preceding points is that yielding to these pressures may frequently do more harm than good. There is a saying that the best is often the enemy of the good, which seems highly relevant . . . The attempt to do more than we can will itself be a disturbance that may increase rather than reduce instability.”

Resolving the Disagreements

So there were two different views: the Samuelson view versus the Friedman view. The fundamental disagreement was not really over which instrument of government policy worked better (monetary versus fiscal), but rather over discretion versus rules-based policies. From the mid-1960s through the 1970s the Samuelson view was winning with practitioners putting many discretionary policies into practice.

But Friedman remained a persistent and resolute champion of his alternative view. At one time during the 1970s, F.A. Hayek even seemed to be siding with the discretionary approach, at least in the case of monetary policy. But Milton Friedman didn’t waver. In fact he sent a letter to Hayek in 1975 saying: “I hate to see you come out as you do here for what I believe to be one of the most fundamental violations of the rule of law that we have, namely discretionary activities of central bankers.” Fortunately, in my view, Friedman’s arguments eventually won the day and American economic policy moved away from such a heavy emphasis on discretion in the 1980s and 1990s.

The Debate Returns

But this same policy debate is back today. Economists on one side push for more discretionary fiscal stimulus packages. They argue that the stimulus packages of 2008 and 2009 either worked or should have been even larger. They also push for more discretionary monetary policy such as the quantitative easing actions. They are not so worried about discretionary bailout policy, discounting the increased moral hazard that lack of a credible rule implies. In these ways they are descendants of the Samuelson school.

Other economists argue for more stable fiscal policies based on permanent tax reforms and the automatic stabilizers. They also push for a return to more predictable and rule-like monetary policy.They argue that neither the discretionary fiscal stimulus packages nor the bouts of quantitative easing were very effective, pointing to the risks of increased debt or monetization of the debt. They worry about the consequences of the discretionary bailouts. In these respects they are descendants of the Friedman school.

Of course there are many nuances today, some related to the difficulty of distinguishing between rules and discretion. You can see this, for example, in discussions of nominal GDP targeting, where some see it as a rule and some see it as a license to proceed with whatever discretionary action it takes. Interestingly, you frequently hear people on both sides channeling Milton Friedman to make their case.

Resolving the Debate Again

While academics are still the main protagonists, the debate is not academic. Rather it is a debate of enormous practical consequence with the well-being of millions of people on the line. Can the disagreements be resolved? Milton tended toward optimism that they could be resolved, and I am sure that this is one reason why he kept researching and debating the issue so vigorously.

Here people on both sides can learn from him. First, while a vigorous debater he was respectful, avoiding personal attacks and never failing to answer a letter. Second, he had a strong believe that empirical evidence would bring people together. He was influenced by statistician Leonard (Jimmie) Savage: Yes, people would come to the issue with widely different prior beliefs, but their posterior beliefs—after evidence was collected and analyzed—would be much closer. In this way the disagreement would eventually be resolved. I think we saw this in the late 1970s and the basic agreements lasted for at least two decades.

Unfortunately, posterior beliefs in the macro area now seem just as far apart as prior beliefs were 50 years ago. Clearly we have a lot of work to do, and clearly we can learn a lot from Milton Friedman in deciding how to proceed.

Posted in Monetary Policy

Comments Off on Still Learning from Milton Friedman

Benefits of More Fed “Action” Do Not Exceed Costs

Both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal ran front page stories yesterday reporting that the Fed is yet again about to take action. “Fragile Economy Said to Push Fed to Weigh Action” said the Times. “Fed Moves Closer to Action” said the Journal. Both stories report that the benefits of such actions in the past have exceeded the costs, but there is precious little evidence for this. In an interview in the latest issue of MONEY Magazine I was asked about this:

What’s your assessment of the Federal Reserve’s recent actions to help spur the economy? The Fed has engaged in extraordinarily loose monetary policy, including two round s of so-called quantitative easing. These large scale purchases of mortgages and Treasury debt were aimed at lifting the value of those securities, thereby bringing down interest rates. I believe quantitative easing has been ineffective at best, and potentially harmful.

Harmful how? The Fed has effectively replaced large segments of the market with itself—it bought 77% of new federal debt in 2011. By doing so, it creates great uncertainty about the impact of its actions on inflation, the dollar and the economy. The very existence of quantitative easing as a policy tool creates uncertainty and volatility, as traders speculate on whether and when the Fed is going to intervene again. It’s bad for the U.S. stock market, which is supposed to reflect the earnings of corporations.

On a more technical level, the latest issue of the International Journal of Central Banking published an article by Johannes Stroebel and me raising doubts about the benefits of the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) purchase program (part of QE1), and the costs of the resulting large balance sheet go well beyond concerns about inflation.

Posted in Monetary Policy

Comments Off on Benefits of More Fed “Action” Do Not Exceed Costs

One of the Most Important Lessons of Modern Macroeconomics

I completely agree with John Cochrane when he writes in his review of my book First Principles that the “preference for rules is one of the most important lessons of modern macroeconomics” and that it is still the major point of disagreement among those writing about economic policy today. As John nicely puts it, the disagreement is about “rules vs. discretion, commitment vs. shooting from the hip, and more deeply about whether our economy and our society should be governed by rules, laws and institutions vs. trusting in the wisdom of men and women, given great power to run affairs as they see fit.”

The disagreement can be seen all over the place. Compare First Principles with Paul Krugman’s End This Depression Now or with Joe Stiglitz’s The Price of Inequality. (All three books published by W.W. Norton, by the way). Many have said that this difference is the main takeaway from the Harvard and Stanford debates between me and Larry Summers.

But even among those of us who agree about the lesson, there are differences in how you go about applying it as John Cochrane points out in reviewing the chapter “Who Gets Us In And Out Of These Messes.” For example, John expresses some skepticism about my proposal to achieve more rule-like behavior in monetary policy through legislation, mainly because the proposal is too “middle-of-the-road,” simply requiring that the Fed report its rule or strategy and narrow its mandate.

I am very open to discussing alternatives, but it is important for the discussion to set the record straight on one point. John Cochrane characterizes my so-called Taylor rule paper published in 1993 as follows: “The Taylor rule was originally an empirical description of Fed actions in the 1980s, a description of how the Fed acted to implement its dual mandate. It only slowly became a normative description of what the Fed should do.” Actually from the start the Taylor rule was meant to be normative. It was the outcome of a search over many years for good policy rules using monetary theory and empirical models with rational expectations and rigidities. And it has only one normative target—a 2 percent inflation rate—along with a process of minimizing fluctuations around that target and around whatever is the given natural rate of output or unemployment.

In any case, the big question is how to apply this “most important lesson.” George Shultz offers some ideas in his interview today in the Wall Street Journal where he emphasizes the importance of rules-based policy with a football game analogy (without predictable rules, no one will play).

Posted in Monetary Policy

Comments Off on One of the Most Important Lessons of Modern Macroeconomics