The recent large impact of U.S. monetary policy on the rest of the world–especially emerging markets–has understandably been attracting a lot of attention in financial markets with headlines like:

Fear of Fed Retreat Roils India, WSJ, Aug 20

Istanbul Skyline Reflects Cheap Dollars Now Growing Scarce, NYT, Aug 21

Currency Depreciation Adds to Brazil Central Bank’s Inflation Worries, WSJ, Aug 21

Fluctuations In Currencies Roil Markets, NYT, Aug 21

The issue also came up yesterday in a press conference in Washington with Mohamed El-Erian, Shelia Bair and me, and it will be a big topic at Jackson Hole with a good paper by Helene Rey.

There are two ways to think about this, as Mohamed summarized at the press conference. (The two views are presented in more detail in a paper I presented last June at the BIS.)

One view is that the US should do whatever it thinks it needs to do to get the American economy growing and this will be the best for the rest of the world. This view is held by people at the Fed and in the Administration. The implication, as Steve Rattner @SteveRattner tweeted yesterday, is that “Emerging markets have no one to blame but selves for their problems.” But it is not a popular view for emerging market central bankers who feel that “whatever it takes” policy is causing a lot of problems for them.

For the other view, consider what El-Erian said yesterday. “We [in the United States] are at the middle, in the middle, of the global system, so we hold it together and therefore when we implement policies we need to think about the feedback loops to the rest of the world. And I think what happened today, to pick up on what John has said, if you look at the newspapers, is that the rest of the world finds it very difficult to navigate a world in which the US is behaving the way it is. And the result of that is that the most powerful engine of growth in the past few years—the emerging world —ok, is slowing down. And the reason why US companies have been able to do well despite the sluggish economy in the US is that they have been selling abroad. And now the risk is that we see increasing policy interference in countries like Brazil, in countries like Indonesia, countries like India, not because they have suddenly become inept, but because it is difficult to navigate in a global system which is so fluid that capital flowing in and out.…And that is very destabilizing to countries that have been pursuing pretty good policies so far.”

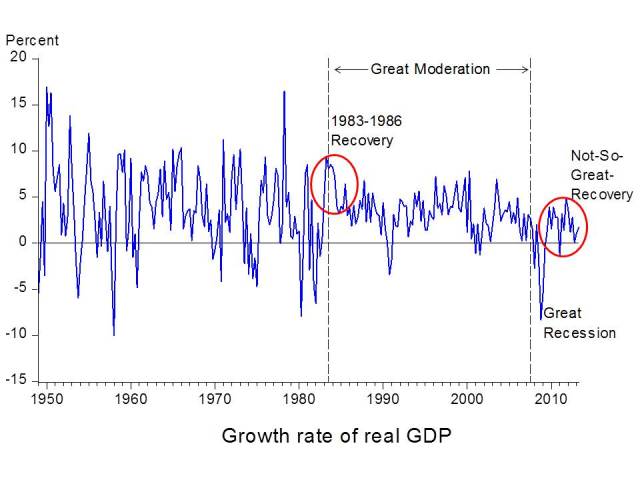

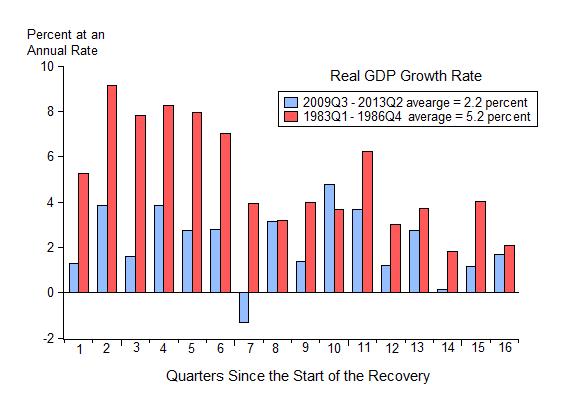

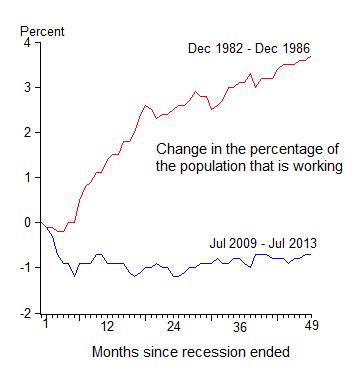

This view—which I share—implies that US behavior–such as the on and off unconventional monetary policies and their impact on capital flows, first out and now back–should at least share some of the blame. The US did not create such problems when it was following more rules-based conventional policies during the great moderation period of the 1980s, 1990s and until recently. Then it was correct to say that the emerging markets had no one to blame but themselves. But many of these countries changed policies for the better. Unfortunately the US also changed policies, but more for the worse.