In response to a question about the policy rules bill at Brookings recently, Ben Bernanke remarked that the “The Fed has a rule.” His claim surprised quite a few people, especially given the Fed’s resistance to the policy rules bill, so he then went on to explain: “The Fed’s rule is that we will go for a two percent inflation rate. We will go for the natural rate of unemployment. We will put equal weight on those two things. We will give you information about our projection, our interest rates. That is a rule.” But the rule that Bernanke has in mind is not a rule for the instruments of the kind that I and many others have been working on for years, or that Janet Yellen referred to in speeches over the years, or that Milton Friedman made famous.

Rather the concept that he has in mind is called “constrained discretion,” a term which he dubbed long ago in an effort to distinguish it from the idea of a rule for the instruments such as Milton Friedman’s which he sharply criticized. Bernanke first used the term in a 1997 paper with Rick Mishkin and later in a 2003 speech shortly after joining the Fed board. In fact, it is a concept he has favored from before the time that I first presented the Taylor rule.

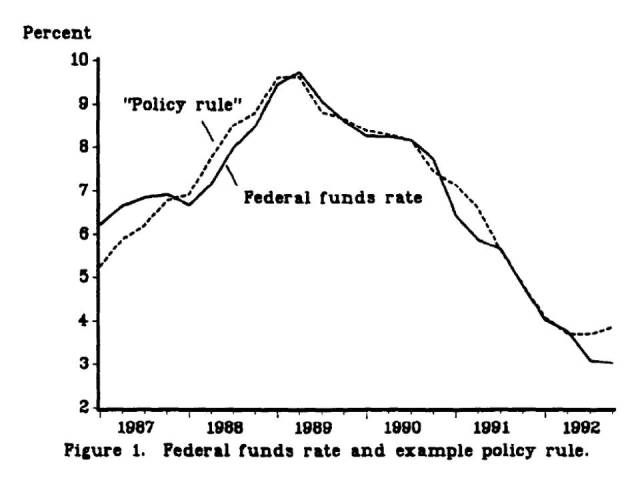

It is that all you really need for effective policy making is a goal, such as an inflation target and an unemployment target. In medicine, it would be the goal of a healthy patient. The rest of policy making is doing whatever you as an expert, or you as an expert with models, thinks needs to be done with the policy instruments. You do not need to articulate or describe a strategy, a decision rule, or a contingency plan for the instruments. If you want to hold the interest rate well below the rule-based strategy that worked well during the Great Moderation, as the Fed did in 2003-2005 after Bernanke joined the board, then it’s ok as long as you can justify it at the moment in terms of the goal.

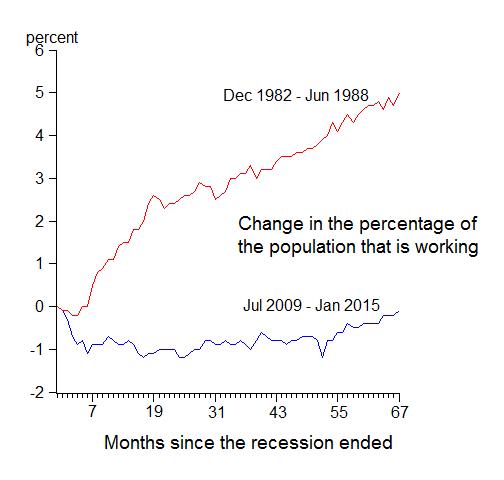

“Constrained discretion” is an appealing term, and it may affect discretion in some sense, but it is not inducing or encouraging a rule as the language would have you believe. Simply having a specific numerical goal or objective function is not a rule for the instruments of policy; it is not a strategy; it ends up being all tactics, all discretion. Bernanke obviously likes the approach in part because he believes “the presumption that the Taylor rule is the right rule or the right kind of rule I think is no longer state of the art thinking.” There is plenty of evidence that relying solely on constrained discretion has in fact resulted in a huge amount of discretion, and that has not worked for monetary policy. David Papell and his colleagues have shown empirically that it is during periods of rules-based policy, rather than periods of so-called constrained discretion, that economic performance has been good.