In the latest edition of his excellent series of podcast interviews, Russ Roberts asked me toward the end what I thought about being characterized as anti-Keynesian as I was in this Economist post The rise of the anti-Keynesians. In a follow-up to the Economist article, David Altig, with basic agreement from Paul Krugman, argued that it was a misnomer because I developed and used macro models (now commonly called New Keynesian) with price and wage rigidities in which the government purchases multiplier is positive (though usually less than one), or because the Taylor rule includes real variables in addition to the inflation rate. In my view, rigidities exist in the real world and to describe accurately how the world works you need to incorporate such rigidities in your models, which of course Keynes emphasized. But you also need to include forward-looking expectations, incentives, and growth effects—which Keynes usually ignored.

In my view the essence of the Keynesian approach to macro policy is the use by government officials of discretionary countercyclical actions and interventions to prevent or mitigate recessions or to speed up recoveries. Since I have long been critical of the use of discretionary policy in this way, I think the Economist is correct so say that I am anti-Keynesian in this sense of the word. Indeed, the models that I have built support the use of policy rules, such as the Taylor rule for monetary policy or the automatic stabilizers for fiscal policy, which are the polar opposite of Keynesian discretion. As a practical prescription for improving the economy, the empirical evidence is clear in my view that discretionary Keynesian policy does not work and the experience of the past three years confirms this view.

Milton Friedman wrote a wonderful review essay on Keynes’ influence on economics and politics which touches on these issues and is still well worth reading. Friedman distinguished between Keynes’ political bequest—the advocacy of discretionary actions taken by powerful government officials—and his economic bequest—the emphasis on aggregate demand as a source of business cycle fluctuations. In the last section of the essay Friedman argues—quoting extensively from Keynes’ famous letter to Hayek on the Road to Serfdom—that the political bequest was very harmful while the economic bequest has many important insights. For simlar reasons using rational expectations models with rigidities or advocating policy rules which react to real economic variables is not inconsistent with an anti-Keynesian or rules-based approach to policy in practice.

This means that the backdrop used two years ago by the “

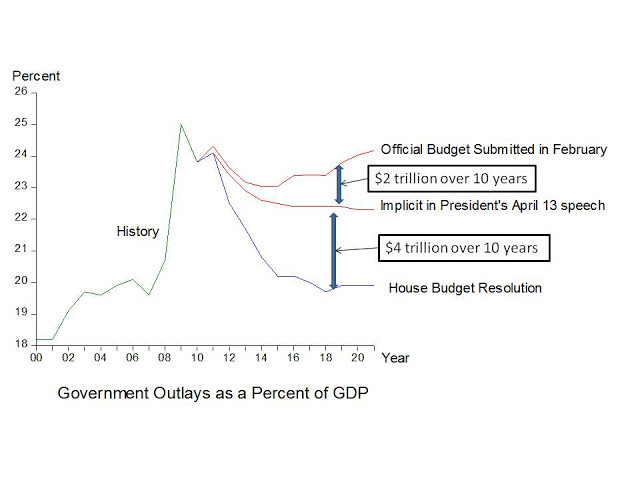

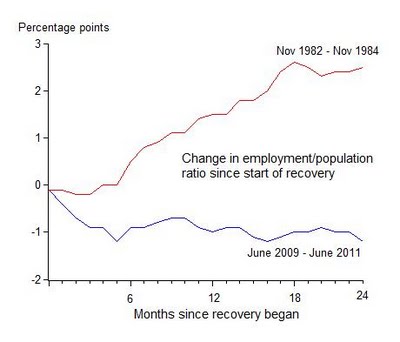

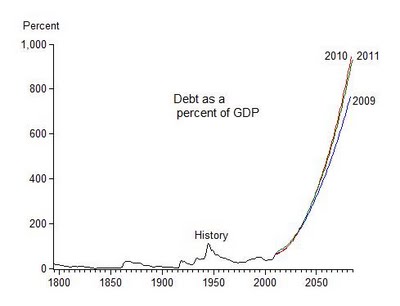

This means that the backdrop used two years ago by the “ Today the Joint Economic Committee of the Congress held a hearing on whether a credible plan to reduce government spending growth would bolster or hinder the recovery. I argued that a credible budget strategy would strengthen the recovery, by removing the threats of another fiscal crisis, higher taxes, higher inflation and higher interest rates—all caused by the huge deficits and growing debt and all impediments to private investment and job creation (written testimony

Today the Joint Economic Committee of the Congress held a hearing on whether a credible plan to reduce government spending growth would bolster or hinder the recovery. I argued that a credible budget strategy would strengthen the recovery, by removing the threats of another fiscal crisis, higher taxes, higher inflation and higher interest rates—all caused by the huge deficits and growing debt and all impediments to private investment and job creation (written testimony