Recently I had the opportunity to participate in several conferences on monetary policy: the annual Hoover monetary policy conference at Stanford in May, the 2019 Fed Review conference in Chicago in June, and the Macro Model Comparison Conference in Frankfurt also in June. There are many takeaways, but one was very evident. I will call it a “Revival of Research on Monetary Policy Rules for the Instruments.” Policy rules were the subject of much research in the 1970’s, 1980’s and 1990’s, but in recent years there was a lull. Now there’s a big pickup. Here are some examples, with the many links found at the conference web pages.

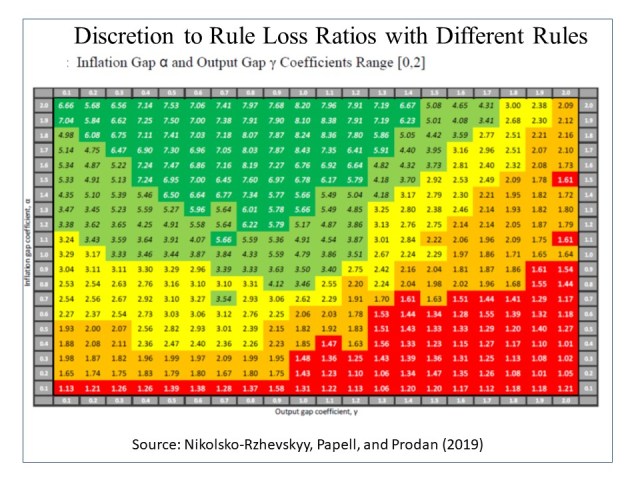

At Stanford, Mertens and Williams (2019) evaluated different interest rules with a new Keynesian model and Cochrane, Taylor and Wieland (2019) evaluated rules with seven different models. In Chicago, Sims and Wu (2019) evaluated different monetary policy rules with a new structural model, and Eberly, Stock and Wright (2019) evaluated monetary policy rules using the FRB/US model. In Frankfurt, Andreas Beyer (2019), Gregor Boehl (2019) and many others evaluated interest rate rules in specific models, and Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, Papell and Prodan (NPP) (2019) compared policy rules with discretion historically using new econometric techniques. NPP considered a specific policy rule for the interest rate and measured discretion as deviation of actual interest rate from that rule. They did calculations for 400 rules and found that the average loss in high deviation periods was greater than the average loss in low deviations periods. They also noted that “inflation-tilting” rules result in better performance. This matrix summarizes their results.

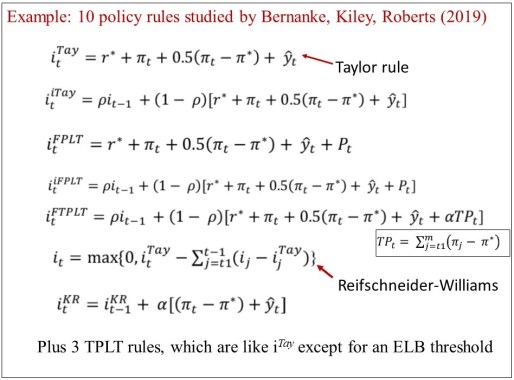

And the evidence goes beyond these conferences. Some have looked at other instruments such as the money supply, including Belognia and Ireland (2019), but most others continue to look at interest rate instruments. Bernanke, Kiley and Roberts (2019) examined ten different monetary policy rules for the instruments using the FRB/US model. The ten interest rate rules are in this table:

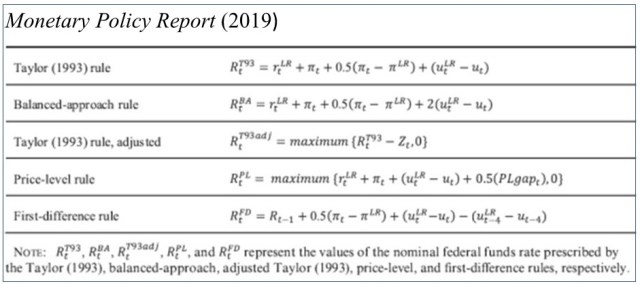

And a whole new section on monetary policy rules for the instruments appeared in the Fed’s Monetary Policy Report (2019) with five different policy rules presented and compared with actual policy. This is the fourth time in a row that such explicit discussion of rules has appeared in the Report effectively in real time. Here are the rules:

What explains the revival? One explanation is simply a revealed preference for such research on the part of monetary policy officials and others interested in monetary policy making. At the Chicago Fed conference, Cecchetti & Schoenholtz (2019) found “The most frequently mentioned topic is the desirability of having a clear understanding of policymakers’ reaction function.” And there are statements by central bank leaders: including Raghu Rajan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, “what we need are monetary rules,” Mario Draghi: “we would all clearly benefit from…improving communication over our reaction functions…” and Jay Powell “I find these rule prescriptions helpful”

Another explanation is the desire to figure out how to deal with the effective or zero lower bound on the interest rate. There is genuine concern at the Fed about the lower bound in the case of a need for substantial easing. How else can one evaluate alternative proposals for “lower for longer” policy, such as the Reifschneider-Williams proposal, than with a rule? This is a huge motivation behind the work presented by Lilley and Rogoff (2019) and Bordo and Levin (2019) at the Hoover monetary conference.

Another explanation is the disappointment with monetary policy leading to great recession and especially the deviation from rules in the 2003-2005 “too low for too long” period.

Another explanation is the recognition that we need rules to evaluate quantitative easing proposals. At the Chicago conference, Brian Sack (2019) said “‘Talking more about the policy rules…is appropriate’ to guide future bond purchase programs and improve their impact.”

Perhaps concern about the proposed Policy Rules Legislation in Congress in 2017-18 led the Fed to talk more openly about policy rules in the Monetary Policy Report.

And finally, there are more people kibitzing about policy, but often without a monetary framework. Rules-based policy analysis provides an explicit and accountable answer to those critics.

There are key features of the revival: Monetary policy rules are usually stated in terms of policy instruments. Generally, they are not “forecast targeting,” which is specific about the goals, such as 2% inflation, but not about the policy instruments. There are very few rules which assume the instrument is QE. An exception is Sims and Wu (2019), who propose a Taylor rule for QE. Perhaps this aversion to rules with QE is due to doubts about impact of QE. Bordo and Levin (2019) say that “Our empirical analysis indicates that QE3 was not an effective form of monetary stimulus,” and Hamilton (2019) argues that QE had little effect.

Another feature is that recent policy rule research, such as in Fed’s Monetary Policy Report, assumes the Taylor principle with the coefficient on inflation greater than 1. As stated in the Report: “One key principle is … the policy rate should be adjusted by more than one-for-one in response to persistent increases or decreases in inflation.

To sum up, there is evidence of a revival of research on rules for the policy instruments whether at conferences, in research papers, and in Fed publications. Possible explanations include revealed preference by policymakers, the need to deal with the effective lower bound, disappointments with past departures from rules, and threats of legislation.

Thus far there has been little work on policy rules with QE as the instrument, perhaps because of doubts about the effect of QE. In any case, there is a great need in this revival for more robustness studies and for international monetary models.

Pingback: Rules Are Back In The Fed’s Monetary Policy Report | Economics One